I still ❤️ you, GOPATH

The newest release of Go – Go 1.13 – finally introduced full support for Go Modules – brilliant and long-awaited solution for built-in dependency versioning problem. Modules now enabled by default, and virtually make GOPATH obsolete.

Technically speaking, GOPATH is still supported, and Go 1.13 Release Notes uses term “GOPATH mode” (as being opposite to the “modules mode”), but still, to me this is a tectonic shift in the Go development ecosystem evolution. Now you or your static analysis tools no longer can assume that all code lives in one large directory.

A lot of people ardently hate the mere idea and the concept of GOPATH. Thousands of people were spending hours trying to configure a single environment variable before starting with Go (no comments on that). Not surprisingly, the fact that you can now work on Go programs in any directory was cheered upon quite vocally.

And yet.

If you ask me, GOPATH was a beautiful and elegant solution to the array of complicated problems and shaped Go ecosystem in a peculiar and unique way.

So, before we sunset GOPATH, I want to pay a little homage to these 6 letters, that brought so much joy to some, and so much frustration to others.

GOPATH: a single config

I’ll start with every newcomer’s entry-point to any language – configuring the development environment.

For most programming languages it was not unusual to spend a day or two just on setting up the environment before you could write a first “hello, world” app. In some languages sophisticated tooling has emerged to detect and find needed binaries and library versions, to accommodate to the OS specifics and machine architecture. In others, it was the responsibility of the developer to properly set up all directories, system variables, paths, filesystem permissions and versions of auxiliary tools manually. Successful companies were conceived by solving this immensely overcomplicated task of setting up a development environment.

So, configuring the new computer for a new programming language has always been a tremendously complicated thing. It was part of the game, though. Everybody knew it’s just how the world works.

GOPATH reduced this whole question to setting up one single value – just tell Go where your working directory is, and the rest is on us. Pick the directory, set the env var, and be 100% sure that your filesystem isn’t touched anywhere else by Go.

What can be easier?

While being that simple, GOPATH gave a confidence in what Go is actually doing to your filesystem. There were no obscure dot-files around the machine, nor system-wide directories configure in platform-specific way – just one directory you’ve chosen and control.

It was clear, easy and refreshing.

In my opinion, part of this clarity was lost when GOPATH acquired its default value (~/go) – new users were no longer required to understand the concept of a single directory workspace.

GOPATH: naming conventions

As a follow-up, GOPATH offered a simple and clean structure for your directory - bin/, pkg/ and src/ triplet. The purpose of each is obvious, and you can infer it from the name.

Down the directory depth, the structure was mirroring Go import names, which were mirroring URL of the version control system for the package.

When I first discovered this naming convention in Go, I was excited and ashamed at the same time – why didn’t I figure out this nice structure myself for other projects?!

You see, in my pre-Go era my home directory, omitting non-development stuff, has been quite a mess – directories like ~/Work/, ~/Projects/, ~/CompanyName/, ~/Soft, ~/ImportantProjectA and alike were shaping the layout of my typical development setup. Of course, folders like ~/Soft and ~/Project has been a huge pile of quickly forgotten names and name-version tuples. What’s important there was no easy way to restore where this particular project came or was downloaded from.

People complain about never uninstalled apps on smartphones? You should’ve seen my HOME directory before GOPATH! :)

GOPATH idea of having one place for all code, structure by URL of its VCS was ingenious and useful from day 0. Finding where the package source lays on disk knowing it’s remote git URL or Github page was a no-brainer now. So is the reverse action – finding the URL of the original source just by looking at the folder path.

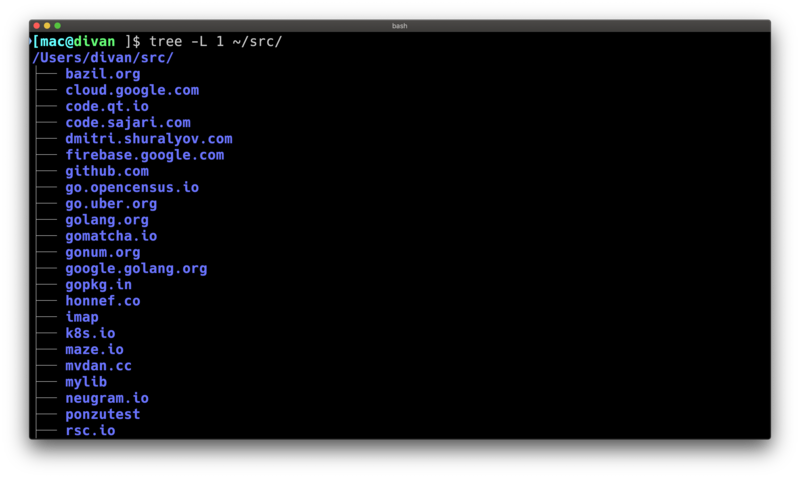

Very soon, I found myself using GOPATH for software projects in other languages itself. I changed GOPATH to point to my HOME directory, and now all the software I ever touched was placed under ~/src in folders structured to mirror their Github URL.

GOPATH made my filesystem much more organized and cleaner. I still use this setup today for everything, and can’t imagine any better layout. Change my mind.

GOPATH: hacking code

Next, the point I haven’t appreciate enough until started hacking with Go static analysis tools – it’s how easy GOPATH made the job of code analysis tools’ authors. No system-wide special directories that change from one OS to another, no separate directories for different Go versions, no version solving problem (that’s my favourite, haha) – it’s just a single environment variable, just do os.Getenv() and you have access to all the code you need.

It made life easier for us, humans, too. You, know, unless you work for NASA, software development is rarely one-way translation of the spec into the code. It’s almost always a two-way process, a tinkering and an experimentation, a creation and discovery, it’s like Escher’s drawing hands – hands drawing the hands, drawing the hands. We need the ability to change parts of the program and its dependencies quickly, see how it changed the behaviour, update our mental models and update the code and so on.

This easy hacking capability is often underrated and underappreciated. GOPATH made this task a breeze – just jump to any code in your editor, change it, check the result, and then decide what to do. It could be just debug printf statement or potential fix of the dependency that will go directly to the pull-request from your change. You could do this not leaving your editor window.

With GOPATH I was always sure in two things:

- I’m able to change/modify my dependencies as much as I want

- I know exactly where the file I’m modifying is on the filesystem

That gave pleasant confidence in this day-to-day process.

GOPATH: making the ecosystem alive

Finally, one of the most subtle and hard to explain points. GOPATH, as you know, didn’t try to solve the versioning problem. It was postponed and offloaded to the third-party tools, and ultimately resulted in Go Modules.

It was an absolutely brilliant solution, though – if the probability of making suboptimal solution multiplied by costs of doing it is higher than costs of not having the solution at all – prefer not to provide the solution at all. It’s a genius akin to Bitcoin’s approach to solving the digital identity problem for digital finance systems – there is no identity. With GOPATH, there is only one ‘master’ version, and that’s it.

That was painful for projects that need semi-reproducible builds in non-monorepos (which seems to be the majority of the small-to-medium codebases in the industry) but was an absolute blessing for the monorepos and open-source software – which is, in a way, also just a one giant monorepository. It was a blessing in one non-obvious way – it created an incentive to keep your code always up to date and in sync with its dependencies.

Invisible incentives

Let me elaborate on it because I foresee this to be debated – no-versions approach with GOPATH created incentives to keep your dependencies updated. As a maintainer of the open-source library, I’m interested that at any point users can do go get and it compiles with all latest versions of dependencies.

After a couple of “doesn’t build” issues and/or pull requests, whatever your prior understanding was, but you start realizing that costs of maintaining dependency are non-zero, to put it mildly, and next time you add yet another leftpad library to your code, you think twice. At some point, you naturally embrace “little copying is better than a little dependency” proverb.

You also start realizing that other projects may depend on your library and you don’t want to break their code unless it’s security fix or absolutely necessary change that cannot be done in any other way. Somehow, you embraced Go1 compatibility promise as a bar for your Go projects too.

GOPATH created the incentive to come to these conclusions naturally.

Talk to humans

Many dependency problems that typically solved by locking versions can be solved by talking of one human to another human. Not always, but more often than you might think.

Some API breaks can be solved by proposing an alternative design or keeping pieces of old API for legacy reasons. Maybe the author didn’t realize that someone depends on her project and wasn’t aware that new change breaks someone’s build. Just talk to the author, maybe she will be happy to find a better solution that doesn’t break API, or keep both, or find some other solution, or help you make a transition.

I’m surprised how little we appreciate the power of human talking to each other in the open-source world. It’s cooler than locking versions.

GOPATH represented much more than just a large directory. It was a little copy of Go universe on your disk. It was a mirror of the subset of Go ecosystem on your machine, and it was alive.

Final words

Millions of GOPATHes on our machines – yours, your coworkers, Go authors, mine – were copies of that ecosystem, and we tried to keep it in sync with each other. Our desire to keep libraries intact and in sync with master branches of other versions was our consensus protocol. And it shaped the dynamics of the Go ecosystem dramatically different from many others.

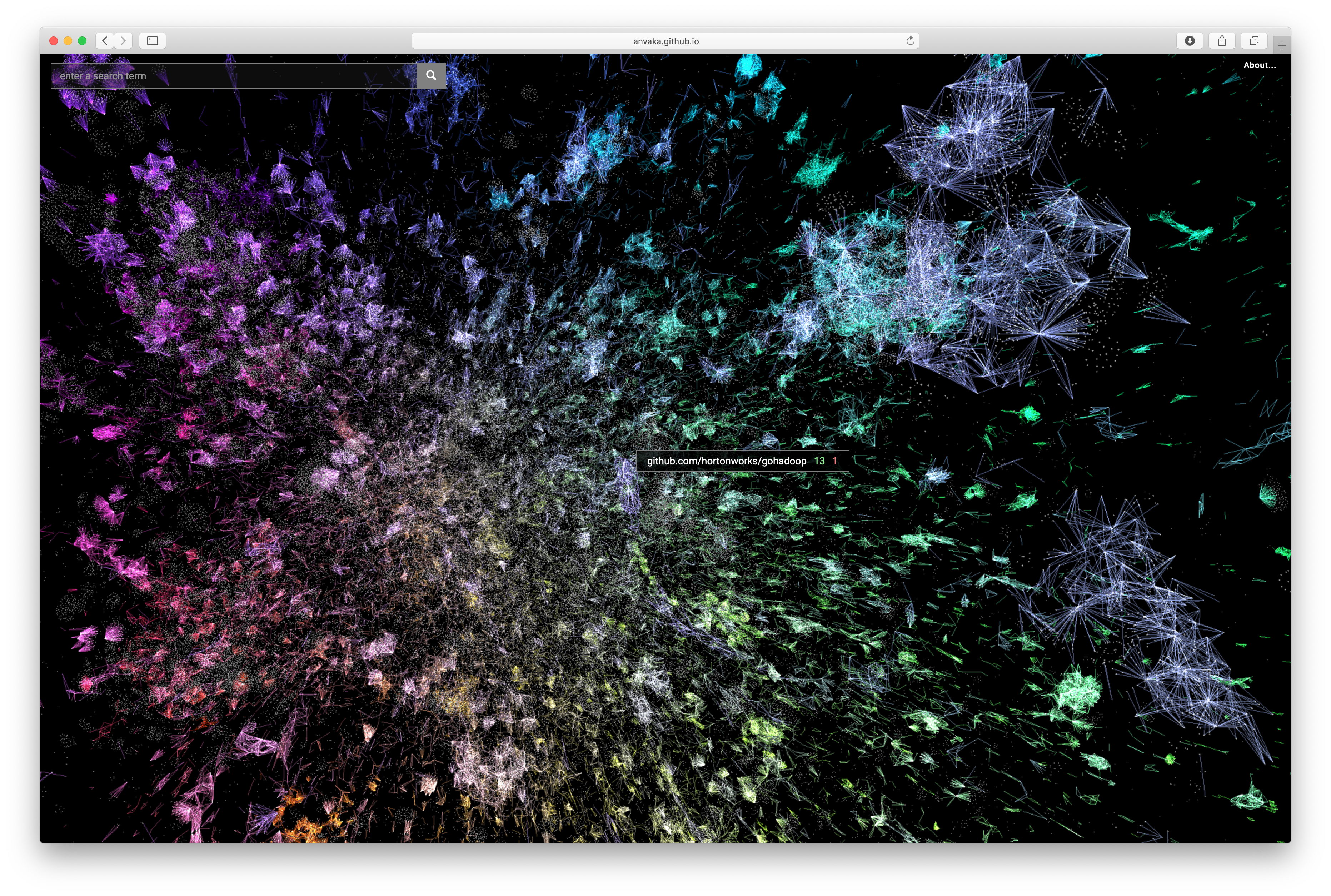

Take a look at the fantastic visualization of the Go universe by Andrei Kashcha:

Some of these dots are your packages. Packages you contributed to. Packages you use in your projects.

They are grouped, clustered, and connected through many more invisible nodes of this graph which are end-user programs, that sit in the private and corporate repositories or never leave the boundaries of your machine. But they still connecting those dots together, making Go ecosystem a huge living organism.

Without your GOPATH that living organism wouldn’t exist.

I’m not sure how alive that organism will be after we say goodbye to GOPATH. Will there be enough incentives to keep this giant beautiful living thing alive and connected?

I still love you, GOPATH.