Fountain codes and animated QR

(source: Anders Sune Berg)

(source: Anders Sune Berg)

In the previous article I’ve described a weekend project called txqr for unidirectional data transfer using animated sequence of QR codes. The straightforward approach was to repeat the encoded sequence over and over until the receiver gets complete data. This simple repetition code was good enough for starter and trivial to implement, but also introduced long delays in case the receiver missed at least one frame. And in practice, it often did, of course.

This sort of problems of sending data over a noisy communication channel is quite well studied, and there is a whole theory exists to deal solve it – coding theory.

In the comments to the previous article, Bojtos Kiskutya mentioned LT codes that can yield much better results for txqr. That was exactly the type of comments I expect – not only suggestion for improvement, but also discovering some new and exciting stuff. And as I have never heard about LT codes before, next couple of days I’ve spent reading everything I could find about them.

It turned out, LT codes (LT stands for Luby Transform) are just one of the implementations of the broader family of codes called fountain codes. It’s a class of erasure codes that can produce a potentially infinite amount of blocks from the source message blocks (K), and it’s enough to receive slightly more than K encoded blocks to decode the message successfully. The receiver can start receiving blocks from any point, receive blocks in any order, with any erasure probability – fountain codes will work as soon as you received K+ different blocks. That’s where name “fountain” comes from, actually – fountain’s water drops represent encoded blocks, and you just have to fill the bucket with enough drops, without actually caring which drops exactly you get.

That was a perfect match for my case, so I quickly found Go based implementation google/gofountain, and replaced my naive repetition code with Luby transform code implementation. Results were quite impressive, and in this post, I’ll share details about LT algorithm, gotchas in using gofountain package and the final results with comparison with original ones.

Fountain codes are damn cool

If you, like myself, have never heard about fountain codes before, don’t worry – they are relatively new and solve very narrow and specific problem. They’re also extremely cool. They beautifully harness properties of randomness, mathematical logic and clever probability distribution tuning to achieve their goal.

While I’m going to describe mostly LT codes, there are many other algorithms in this family – Online codes, Tornado codes, Raptor codes, etc., with Raptor codes being superior in almost every aspect, excluding a legal one. They seem to be heavily covered by patents and not widely implemented.

So the idea behind LT codes is relatively simple – encoder splits message into source blocks , and continuously creates encoded blocks that consist of 1, 2 or more randomly selected source blocks XOR-ed with each other. Block IDs used to construct each new encoded block are stored in it in an arbitrary way.

Decoder, in its turn, collects all the encoded blocks (like a drops from a fountain) – some consisting from just 1 source block , some from 2 or more – and tries to restore new blocks by XORing them back with already decoded blocks.

So when decoder sees the encoded block with just 1 source block – it does nothing else than adding it to the list of decoded blocks. Once it catches the block with 2 XOR-ed source blocks , it checks the IDs, and if one of them is already in the list of decoded blocks – easily restore it due to the property of XOR. The same applies to decoding encoded blocks with more than 2 source blocks – once you have all but one blocks decoded – just XOR it.

Solition distribution

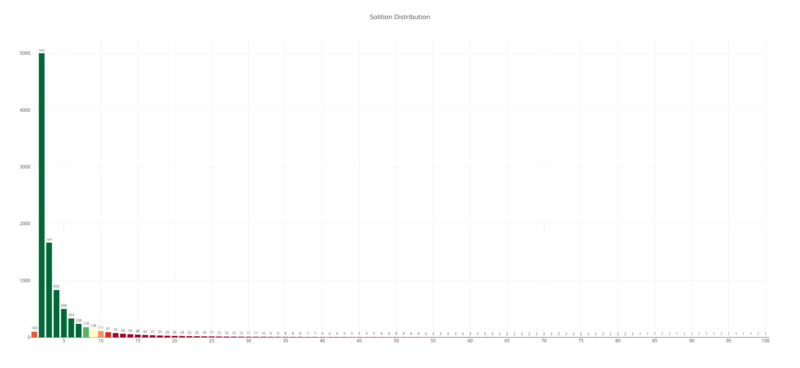

The coolness lays in choosing how to decide how many blocks should be encoded with just 1 source block , with 2 or more. Too many single block packets and you lose the redundancy needed. Too many multiple-blocks packets – and it’ll take too much time to get single blocks in a very noisy channel. That’s what Michael Luby, after which Luby codes are named, calls the Solition Distribution - almost perfect distribution, which ensures that you have enough single block packets, definitely have a lot of 2-blocks packets and also a long tail of many-blocks packets up to N-block ones, where N is the total amount of source blocks .

Here is a closer look at the head of the distribution:

You can see here some non-zero amount of single block packets, then 2-blocks packets take a fair share of all distribution (it’s exactly a half to be precise), and the rest is distributed in descending way between the packets with a higher number of XOR-ed blocks.

All that give LT codes a lovely property of not depending on how often or in which pattern communication channel loses packets.

For my txqr project, it means that fountain code should give on average much lower decoding time with any given encoding/transmission parameter.

google/gofountain

The google’s package gofountain implements several fountain codes in Go, including Luby transform code. It has tiny API (which is a good sign for the library) – basically just Codec interface with a few implementations and EncodeLTBlocks() function, plus a few pseudorandom generators helpers.

However, I stuck while trying to understand what does the second parameter of EncodeLTBlocks() is supposed to mean:

func EncodeLTBlocks(message []byte, encodedBlockIDs []int64, c Codec) []LTBlock

Why would I want to provide block IDs to the encoder, I don’t even want to worry about blocks’ properties, as it’s an algorithm implementation and not the library user’s concern. So my first guess was just to pass all block IDs – 1..N.

It was close enough – debug output from tests produced blocks that looked like what I expected, but decoding had never been finishing.

I checked GoDoc page for gofountain to see what other packages use it, and found only one open-source library for transmitting large files over lossy networks - pump by Sudhir Jonathan, I decided to leverage the power of friendly Gophers community and contacted Sudhir in Gophers slack, asking if he could help me to clarify those IDs usage.

And that worked, Sudhir was extremely helpful and gave me an elaborate answer, which clarified all my doubts. The right way to use this library was to pass incremental IDs for blocks continuously – for example, 1..N, N..2N, 2N..3N, etc. As generally we don’t know how noisy the channel is, it’s important to generate new blocks all the time.

So proper usage would be to generate chunks of IDs, and call EncodeLTBlocks in a loop. But in order to achieve that, I had to ensure that QR encoding speed is good enough to generate new blocks on the fly. For 15 frame per second rate, the total time for encoding next block and generating a new QR code should be less than 1s/15 = 66ms. Which is obviously doable, but would require careful benchmarking and optimizing to ensure this is true for GopherJS-transpiled version on single core in the browser.

Plus, there were current design limitations – txqr.Encode() API expects to return a concrete number of chunks to be encoded as QR frames, plus txqr-tester generate animated GIF file upfront to ensure reliable framerate when displayed in the browser, so, I decided not to break API for now and went with redundancy factor approach.

Redundancy factor approach is based on the assumption that in my case noise estimations is more or less predictable – I’d say no more than 20% of skipped frames. We can generate N*redundancyFactor frames and just loop it over as in repetitive codes approach. This approach is sub-optimal in general case, but for my task and controlled environment it was good enough. So for encodedBlockIDs parameter, I use a simple helper function:

// ids create slice with IDs for 0..n values.

func ids(n int) []int64 {

ids := make([]int64, n)

for i := int64(0); i < int64(n); i++ {

ids[i] = i

}

return ids

}

and call it via:

codec := fountain.NewLubyCodec(N, rand.New(fountain.NewMersenneTwister(200)), solitonDistribution(N))

idsToEncode := ids(int(N * e.redundancyFactor))

lubyBlocks := fountain.EncodeLTBlocks(msg, idsToEncode, codec)

That’s probably a needlessly boring part for the reader not interested in working with gofountain, but I hope it’ll be helpful for someone struggling with its API, coming to this post via search results.

Testing results

As I preserved the API of the initial package, the rest was a breeze. As you might remember from the previous article, I used the txqr Go package in both iOS app and web app called txqr-tester, running in the browser. That’s where mindblowing cross-platform nature of Go paid off again! I just switched to my fountain-codes branch, with the new implementation of encoder and decoder, run go generate to execute both gomobile and gopherjs commands, and in a couple of seconds, I had fountain codes implementation ready to use with Swift and in the browser.

I wonder if there any other language that can do this?

I launched my test setup, consisting of the phone on a tripod and external monitor, configured testing parameters and launched automated testing, which lasted nearly half a day. This time I didn’t change QR error recovery levels to save time, as they seem to have a negligible effect on the result.

The results were more than impressive.

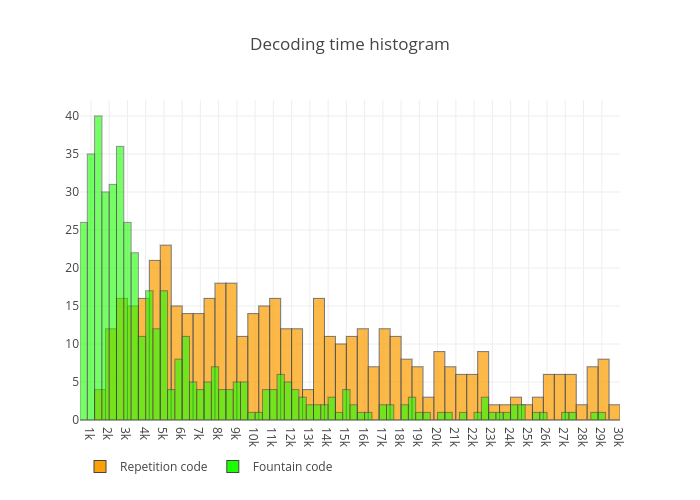

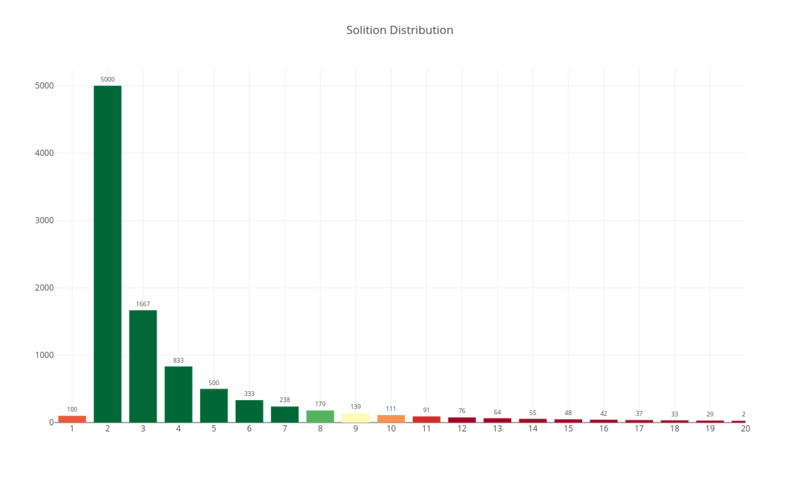

The record time for transferring ~13KB of data is now is half a second or 501ms to be precise – it’s almost 25kbps. This record was set for 12FPS and 1850 bytes per QR code with low error correction level. The variance of the time needed to decode plummeted significantly as there were no “expect the whole loop iteration” part as with repetition codes. Compare decoding times histogram between repetition code and fountain code :

As you can see, most of the decoding attempts, with different values for FPS and chunk size, are still concentrated in the lower part of time axis – most of them less them 4 seconds.

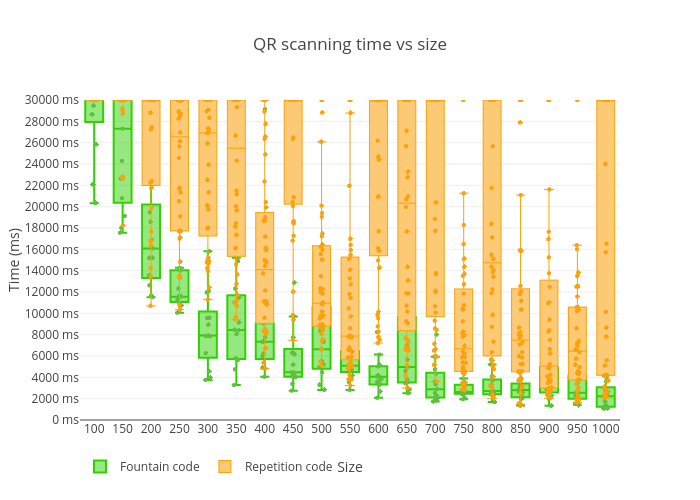

And here is more detailed results breakdown:

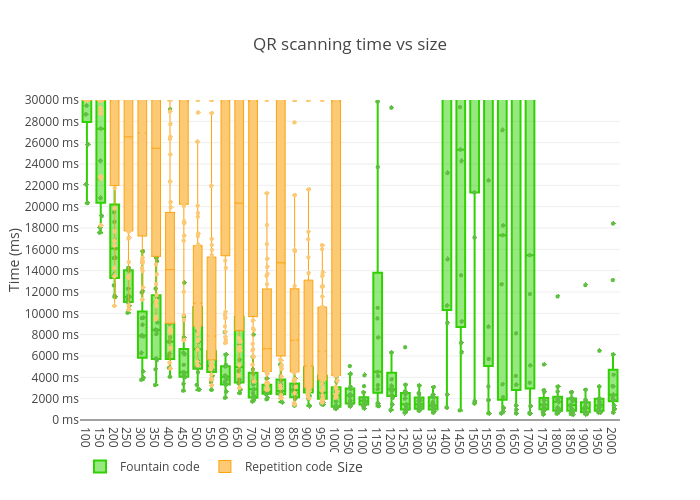

Results were so good, so I decided to run tests with chunk sizes greater than 1000 bytes - up to 2000 bytes. And that brought me interesting results – there were a lot of decoding timeouts with chunk sizes between 1400 and 1700, but 1800-2000 bytes actually showed one of the best results so far:

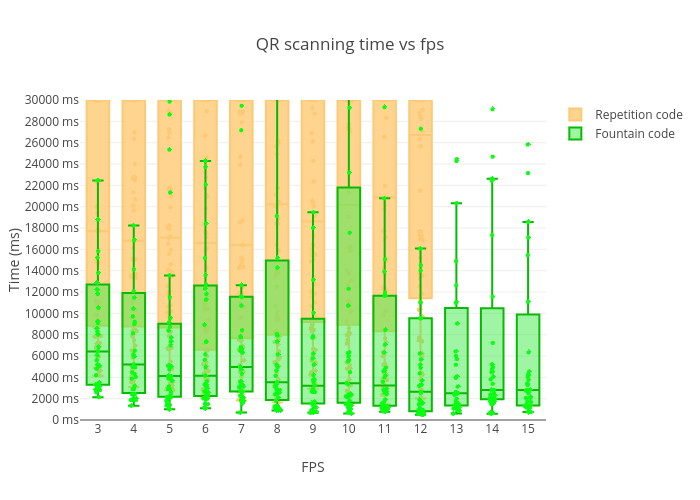

FPS effect seemed to be even more negligible this time but showed much better results within all values overall, and I even was able to increase the upper cap to 15FPS:

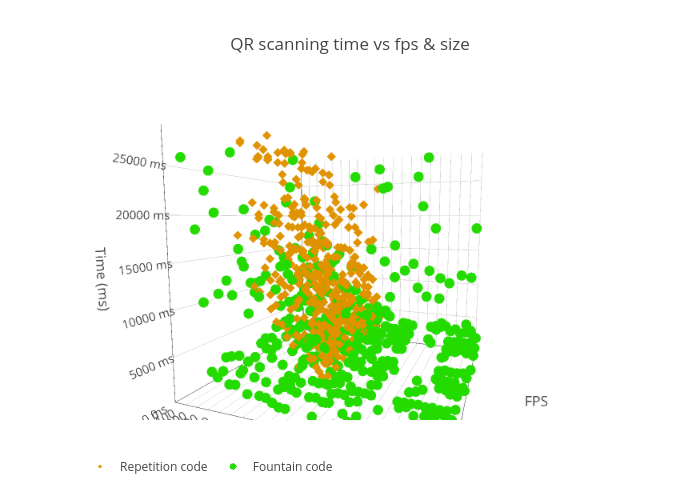

Here is a complete interactive 3D interactive graph with results:

Conclusion

Fountain codes are definitely an exciting thing to work with. Being non-trivial, but simple, narrow scoped, but extremely useful, clever and fast, they undoubtedly fall into the “cool algorithms” bucket. They’re one of those algorithms that can give you awe once you understand how they work.

For txqr, they offered dramatic performance and reliability improvements, and I’m looking forward to play with more efficient algorithms than LT codes, and implement proper API adapted to the streamline nature of fountain codes.

Gomobile and Gopherjs, again, showed their awesomeness by decreasing the hassle of using already written and tested code in the browser and mobile platforms to a lowest possible minimum.